Embedded System have a lifetime of 10 or 15 years. During that time the software and tools has to be maintained. This can be very challenging. Who knows if that compiler or tool used is still available in 10 years from now? Additionally installing and configuring the tool chain and environment for a new team member is difficult. Even worse: using a different host operating system for the cross development can produce different results or introduce issues.

One solution for all these problems is to use Docker images and containers. I can pack all the necessary tools and software into a virtual environment and container. But developing inside a container comes with many challenges. In this article I’ll show how Visual Studio Code or VS Code makes working with containers very easy. In this article I show how easy it is to use modern development tools and methodologies for embedded development.

Outline

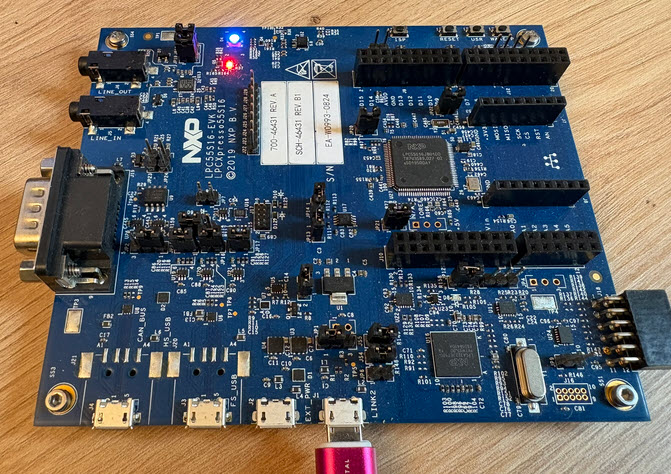

This article explains the concept of VS Code using the DevContainer extension. How to install and use it for embedded application development. I’m using the concept for example to develop for ARM Cortex-M, ARM Cortex A, RISC-V and Tensilica.In this article I’m using the NXP LPC55S16 (ARM Cortex-M33) evaluation board.

In this article I through the basic setup and build process. The more advanced topics like debugging, semihosting, GNU coverage or CI/CD I’m going to cover in another article.

You can find the project and files used in this article on GitHub.

Developing inside a Container

Traditionally, developing inside a container can be very painful. I’m usually limited to use command line tools. This is great for setting up automated builds and for testing. See GitLab Automated CI/CD Embedded Multi-Project Building using Docker or CI/CD for Embedded with VS Code, Docker and GitHub Actions. Containers are great, as they have all the tools and software isolated and installed. It makes it independent of the host OS used. And in many cases building and testing on a Linux system is faster because of its file system.

But what about the code development and debugging? Working on the host is very comfortable: I can use a graphical user interface with VS Code. I have full IntelliSense and code completion and all the nice extensions working. And debugging is very easy with a graphical user interface.

How can I combine the comfort of development on the host with the benefits of running everything in a container? This is exactly what VS Code can do with running with a DevContainer:

It means that I run VS Code with the source code on the local OS (e.g. Windows), but the actual development process with compiling, running and debugging runs inside the container (e.g. Linux). The container runs as a docker container, and all the tools run in the container too.

VS Code runs on the host or local OS, and communicates with a VS Code Server inside the container. The VS Code Server is ‘headless’ and runs its own set of extensions.

The project workspace and source code (e.g. git repository) is physically on the local OS and file system, but gets mounted automatically into running container. The source code is automatically shared between the local OS and the container. Everything else in the workspace is also shared automatically.

The key thing is: with the above approach, I have the same developer experience working with a container. It is just like working on the host! Regardless where my tools (or code) are located.

Prerequisites

I assume you have the following items installed:

- VS Code: https://code.visualstudio.com, see for example VS Code: Getting Started, literally

- For Windows, you need WSL (Windows Subsystem for Linux) installed: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/wsl/install

- Docker: https://www.docker.com/ running a docker deamon. I recommend to install Docker Windows if using a Windows host. Additionally, Docker needes to be configured for WSL, see https://docs.docker.com/desktop/wsl/.

- And embedded target and toolchain for it, for example the NXP LPC55S16. Either with an on-board debug probe, or an external debug probe (for example NXP MCU-Link or SEGGER J-Link).

In this article, I’m not going into details of the above. I assume you have it already installed. You can easily find guidance with the provided web links.

VS Code Extension

The most important extension to use DevContainers is the VS Code ms-vscode-remote.remote-containers extension:

I recommend installing the Docker extension too: ms-azuretools.vscode-docker

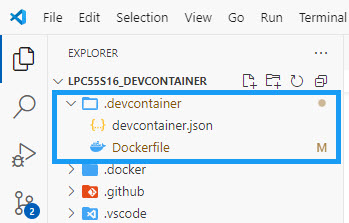

.devcontainer Folder

Development containers are enabled in VS Code with the presence of a folder named .devcontainer:

Usually there are two files in it:

- devcontainer.json configures the development container for VS Code

- Dockerfile is used to build the docker image and container

I will explain the content of two files later on.

Open a DevContainer Project

If you open in VS Code a folder (aka project) in VS Code, and if a .devcontainera folder (with its corresponding files) is present, VS Code offers to ‘Reopen in Container’:

That can be confusing the first time. But you have open the directory with VS Code on the host (so it is ‘open’ on the local OS). Now VS Code recognizes that it is configured to use with DevContainer. It asks if it should re-open that project inside a container.

I can still open it in the local OS, and use it (edit, build, debug) with my local OS. But as a DevContainer project, I can do the same inside a container too. This is what the question about: I can start developing inside a container.

Open in Container

I can open the folder anytime in a container using CTRL+SHIFT+P:

If I open the project in a container, it will build or rebuild the container as needed. So this can take a few minutes the first time.

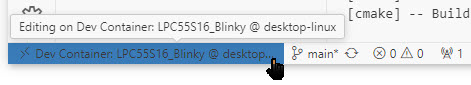

The connection status is visible in the lower left corner of VS Code:

Developing in Container

Developing in the container is the same experience as doing the same thing on the host. Except that one can see that the build is running in the Linux container, and I have a Linux Bash shell running:

The workspace and project files are mounted into the container under /workspace. That way all changes inside the container are applied to the file system on the host.

Open Locally

To open the project locally again, I can click on the connection status and then do ‘Reopen Folder Locally’:

With this, I can easily switch between the host and container.

💡 Remove the build output folder if switching the build platform, because CMake cache is using the other host system.

Next, let’s look into the details to make it work.

devcontainer.json

The devcontainer.json file has the metadata for the container build. See https://containers.dev/implementors/json_reference/ for details.

Below is what I’m using:

// For format details, see https://aka.ms/devcontainer.json. For config options, see the

// README at: https://github.com/devcontainers/templates/tree/main/src/ubuntu

{

"name": "LPC55S16_Blinky",

"build": {

"dockerfile": "Dockerfile" // use local docker file

},

// use a shorter path ("/workspace") for folder in the container.

// This has to be cut of as prefix in semihosting file operations

"workspaceMount": "source=${localWorkspaceFolder},target=/workspace,type=bind",

"workspaceFolder": "/workspace",

// Configure tool-specific properties.

// Set *default* container specific settings.json values on container create.

"customizations": {

"vscode": {

// Add the IDs of extensions you want installed when the container is created.

"extensions": [

"ms-vscode.cpptools",

"mcu-debug.debug-tracker-vscode",

"ms-vscode.cmake-tools",

"ms-vscode.vscode-serial-monitor",

"ms-vscode.cpptools-extension-pack",

"marus25.cortex-debug",

"ms-azuretools.vscode-docker",

"jacqueslucke.gcov-viewer"

]

}

},

// Uncomment to connect as root instead. More info: https://aka.ms/dev-containers-non-root.

// "remoteUser": "root"

"remoteUser": "vscode"

}

With the following the DevContainer gets a name:

"name": "LPC55S16_Blinky",

The next specifies the (local) docker file to be used for building the image:

"build": {

"dockerfile": "Dockerfile" // use local docker file

},

By default, if the workspace is inside a git repository, it will mount the full git repository into the container. With the settings below, I only mount part of the tree into the container as ‘\workspace‘:

"workspaceMount": "source=${localWorkspaceFolder},target=/workspace,type=bind",

"workspaceFolder": "/workspace",

I have the ability to directly install some VS Code extensions into the container, for example:

"customizations": {

"vscode": {

// Add the IDs of extensions you want installed when the container is created.

"extensions": [

"ms-vscode.cpptools",

"mcu-debug.debug-tracker-vscode",

"ms-vscode.cmake-tools",

"ms-vscode.vscode-serial-monitor",

"ms-vscode.cpptools-extension-pack",

"marus25.cortex-debug",

"ms-azuretools.vscode-docker",

"jacqueslucke.gcov-viewer"

]

}

},

Finally, I define the user to be used in the container for VS Code:

"remoteUser": "vscode"

The last thing is important for security too. Otherwise, with a Linux host OS, there are permission issues. These issues occur if the UID/GID does not match. Without a remote user name, ‘root’ is used.

DockerFile

The docker file is used to build the image and container. Here I have to install all the needed software and tools. It does not include the project, as the project sources get mounted into the container.

# Docker file for VS Code using DevContainer

FROM mcr.microsoft.com/devcontainers/cpp:dev-ubuntu24.04

# folder for downloaded files and virtual python environment

WORKDIR /apps

RUN mkdir -p /apps

# Install general prerequisites

RUN \

apt update \

&& apt install -y git python3 wget unzip \

&& apt install -y cmake build-essential ninja-build \

&& apt install -y gcc-arm-none-eabi gdb-arm-none-eabi libnewlib-arm-none-eabi

# Install utilities

RUN apt-get install -y nano iputils-ping udev curl

# Install doxygen and graphviz

RUN apt-get install -y doxygen graphviz

# Get a specific version of the ARM toolchain

RUN \

cd /apps \

&& wget https://github.com/xpack-dev-tools/arm-none-eabi-gcc-xpack/releases/download/v13.2.1-1.1/xpack-arm-none-eabi-gcc-13.2.1-1.1-linux-x64.tar.gz -O gcc-arm-none-eabi.tar.gz \

&& mkdir /opt/gcc-arm-none-eabi-13.2.1-1.1 \

&& tar -xvzf gcc-arm-none-eabi.tar.gz -C /opt/gcc-arm-none-eabi-13.2.1-1.1 --strip-components 1 \

&& rm gcc-arm-none-eabi.tar.gz \

&& ln -s /opt/gcc-arm-none-eabi-13.2.1-1.1/bin/* /usr/local/bin

# for gcov, have to use the arm-none-eabi-gcov one

RUN \

rm /usr/bin/gcov \

&& cd /usr/bin \

&& ln -s /opt/gcc-arm-none-eabi-13.2.1-1.1/bin/arm-none-eabi-gcov gcov

# Install gcovr (needs pip) and virtual environment

RUN \

apt install -y python3-pip python3.12-venv

RUN \

cd /apps \

&& python3 -m venv venv \

&& ./venv/bin/pip install gcovr

# Install SEGGER tools

# in case issue with mismatch between J-Link version between host and container/image: use matching version

RUN \

apt-get install -y \

apt-transport-https ca-certificates software-properties-common \

libx11-xcb1 libxcb-icccm4 libxcb-image0 libxcb-keysyms1 libxcb-randr0 \

libxcb-render-util0 libxcb-shape0 libxcb-sync1 libxcb-util1 \

libxcb-xfixes0 libxcb-xkb1 libxkbcommon-x11-0 libxkbcommon0 xkb-data \

&& cd /apps \

&& curl -d "accept_license_agreement=accepted&submit=Download+software" \

-X POST -O "https://www.segger.com/downloads/jlink/JLink_Linux_V810g_x86_64.deb" \

&& dpkg --unpack JLink_Linux_V810g_x86_64.deb \

&& rm -f /var/lib/dpkg/info/jlink.postinst \

&& dpkg --configure jlink \

&& apt install -yf

# Install LinkServer software: make sure you have the same version installed on your host!

# Linkserver download paths, e.g.

# Windows: https://www.nxp.com/lgfiles/updates/mcuxpresso/LinkServer_24.12.21.exe

# Linux: https://www.nxp.com/lgfiles/updates/mcuxpresso/LinkServer_24.12.21.x86_64.deb.bin

# MacOS Arch64: https://www.nxp.com/lgfiles/updates/mcuxpresso/LinkServer_24.12.21.aarch64.pkg

# MacOS: https://www.nxp.com/lgfiles/updates/mcuxpresso/LinkServer_24.12.21.x86_64.pkg

RUN \

apt-get install -y whiptail libusb-1.0-0-dev dfu-util usbutils hwdata \

&& cd /apps \

&& curl -O https://www.nxp.com/lgfiles/updates/mcuxpresso/LinkServer_24.12.21.x86_64.deb.bin \

&& chmod a+x LinkServer_24.12.21.x86_64.deb.bin \

&& ./LinkServer_24.12.21.x86_64.deb.bin --noexec --target linkserver \

&& cd linkserver \

&& dpkg --unpack LinkServer_24.12.21.x86_64.deb \

&& rm /var/lib/dpkg/info/linkserver_24.12.21.postinst \

&& dpkg --configure linkserver_24.12.21 \

&& dpkg --unpack LPCScrypt.deb \

&& rm /var/lib/dpkg/info/lpcscrypt.postinst \

&& apt-get install -yf

# Command that will be invoked when the container starts

ENTRYPOINT ["/bin/bash"]

The is building an Ubuntu image with the necessary build tools. For the compiler and libraries, an explicit version of the GNU ARM toolchain is used. This is critical for a stable build environment and for reproducability.

Same for the debugging tools: a version of NXP LinkServer and SEGGER J-Link gets installed.

Nothing is perfect

Developing with DevContainer has some advantages and disadvantages. Most embedded developers for MCUs use a Windows host. Therefore, with VS Code DevContainers for Embedded MCU development, the natural choice is Windows on the host. A container running Linux is used.

Advantages of using DevContainer

- Same developer experience working in the container as on the host. I can use VS Code as I would work directly on the host.

- Isolated tools environment setup in container: I can easily switch between the different environments.

- Faster builds inside the container, as Windows firewall and file system on Windows can slow down large builds.

- Shareable ‘projects’: A DevContainer ‘project’ can be easily used on a Linux, MacOS or Linux host.

- Deep control of the docker image and installation process.

Disadvantages of using DevContainer

- Restricted to use Microsoft VS Code.

- Requires Docker (e.g. Docker Desktop running).

- Extra RAM on the host needed to run Docker (~3-5 GB RAM).

- Extra disk space needed for the Docker images and container. This easily can add up several hundreds of GB disk space.

- More complex to to setup, as I need to use and understand Docker.

- Debugging or using USB based debug probes is not easy and needs to use IP based debug probes.

As about debugging: I’m going to cover this in a next article.

Summary

VS Code with DevContainer give me the same developer experience as I would develop on the host, without docker. Using docker container I have isolated and dedicated build and test environment. I can keep projects and environments separated. As the project workspace is mounted into the container, the build and test output is easily shared.

With containers, I can share my projects and development environment easily with others. It gives me an effective way to use the same setup with a Windows, MacOS or Linux host too.

Using DevContainer is more complex and needs more resources on the host because of Docker. However, it is an effective way of development, especially for embedded systems. I can easily switch between different vendor tools and installation ways.

In a next article I’ll cover the more advanced topics, such as debugging or semihosting.

So what do you think? Are DevContainer something you already know or use? Or has this article sparked your interest for taking embedded development to the next level? Let me know your thoughts in the comment section!

Happy containering 🙂

Links

- Microsoft: Developing inside a Container

- Docker: https://www.docker.com/

- GitLab Automated CI/CD Embedded Multi-Project Building using Docker

- CI/CD for Embedded with VS Code, Docker and GitHub Actions

- Files on GitHub: https://github.com/ErichStyger/MCUXpresso_LPC55S16_CI_CD

- Debugging with DevContainer

Containers are undeniably advantageous, providing a good level of isolation and offering several long-term benefits. However, many people (myself included, initially) tend to overlook that containers are merely an advanced chroot environment. They are not standalone but operate on top of an existing, typically modern, kernel. For instance, if you have an Ubuntu 18 container, it does not include the Ubuntu 18 kernel; instead, it runs on the current kernel, say, Ubuntu 24. While Linux kernels boast substantial backward compatibility, there is no assurance that an Ubuntu 18 container will function on an Ubuntu 40 kernel (or whatever its name in the future).

In scenarios where a development environment must be preserved for 10-15 years, a virtual machine may be a more suitable solution, provided that the format used to store the virtual machine remains compatible with the virtualiser in use in 10-15 years, which is also not guaranteed.

Acknowledging the reality that nothing lasts forever, my solution for reproducible environments is the xPack Reproducible Build Framework. It is easier to use than Docker images and generally offers a few good years of stability.

LikeLike

Yes, that’s correct: docker and container run on existing infrastructure. And there is no guarantee that this will continue running even in the next version or year.

I have used xPack occasionally and it is in general a good solution. But I have not been able to use it in a classroom environment, there has been too much resistance against ‘yet another package manager’ solution. A docker environment has been the preferred solution there, as most students were familiar with it.

As for the longevity approach: what we have used successfully for dedicated projects is archiving the developer machine (yes, the hardware with the software/tools!), combined with a backup system. Putting possible issues aside (dead bios clock battery, disk retention, …), that worked so far for projects +10 years old.

LikeLike

I’ve been using Eclipse Embedded CDT in the past with Docker. Switching to VSCode with Docker requires quite a bit of rethinking the development workflow.

First, the difference between Eclipse vs. VSCode Docker support is that Eclipse can support invariant docker images.

i.e., Build a docker image, and attach it to an Eclipse project. The docker image contains only the build tools and nothing else. This allows me to keep the Docker Images up to date or versioned without worrying about the Eclipse version or workspace / source configuration. Eclipse will mount all relevant workspace folders into the Docker Image when executing.

In contrast, VSCode starts with a Docker Image, and MODIFIES it to match the project configuration and setup. This means that VSCode will have lots of containers created as part of the project, more so when the Docker Image configuration was updated, necessitating a new Docker container to be instantiated. Different projects using the same Docker Image configuration will still generate separate docker containers. This leads to a lot of temporary containers that need to be cleaned up from time to time.

Having said all this, Eclipse support for Docker (via the Docker Tooling Plugin) has been trailing updates to Docker Desktop as it is now in maintenance mode. There were two instances of breakage last year alone due to this.

In addition, editing JSON files isn’t my idea of fun, and error prone. However, once it has been setup correctly, VSCode with Docker Containers does work well. The learning curve is something to consider though.

LikeLike

Good points! I have used ‘static’ docker containers too, and you correct about the creation of new docker containers which I have to clean up, otherwise it adds to the disk usage.

The ‘dynamic’ way of VS Code using DevContainer gives the benefit of an easier development flow (if everything works and is correctly setup), and I can easily switch between ‘container’ and ‘local OS’ development too. I would love to use Eclipse more with docker, but it seems that all the cool tooling is moving away from that platform :-(.

LikeLike

question: what guarantees the “headless” server compatibility with extensions? Same say for say segger tools.

Personally I prefer seperate the IDE from the tools required for the compilation; potentially creating several builds and combine them with multi stage builds (not sure its feasible)

For example recipes /image (preferably both) holding the toolchain, make and any other tool or lib required (Specific versions were relevant) that is the basics that allow build without IDE. You can build on that to top it with the VSC server.

LikeLike

VS Code manages the extensions in the container. I don’t know the details behind that, but VS Code seems to manage and update the extension accordingly.

As for the debugger tools (e.g. SEGGER or LinkServer): they are locked down in the container.

As for separation: here the editor (VS Code) and the build tools are separated: the build tools (compiler/etc) are in the container (if using DevContainer).

And all the builds are headless too, and build by command line (bascically it is CMake with Ninja).

As for separating the recipies/images: for simplicity I have put everything in on Dockerfile, but of course this can be structured as you need it.

I hope that makes sense?

LikeLike

Hi Eric,

As always, an excellent and informative article! Thank you very much!

I noticed problems getting the stuff running.

I think in the docker file on GitHub, I assume the statement to create the `vscode` code is missing:

`RUN useradd -m vscode && chsh -s /bin/bash vscode`

Otherwise, it will not start up as devcontainer, since there the user `vscode` is used.

Thank you.

Best Regards,

Michael Kiessling

LikeLike

Hi Michael,

thank you!

About the vcode user: are you using the same as I do?

FROM mcr.microsoft.com/devcontainers/cpp:dev-ubuntu24.04

as well? Because as far as I see there the user ‘vscode’ already has been used, so I had no issue creating the docker file as DevContainer.

Thanks!

Erich

LikeLike

Hi Eric,

the Dockerfile on GitHub, is using `FROM ubuntu:24.04` while in the article you use`FROM mcr.microsoft.com/devcontainers/cpp:dev-ubuntu24.04`and I started with the setup from GitHub. with-out comparing both intensively. 👍

So I mixed it up! Thank you for clarification. Best RegardsMichael

LikeLike

Hi Michael,

The Dockerfile in the root folder of the project is if you create a container manually.

The one used bye VS Code and DevContainer is the one inside .devcontainer folder as outlined in the article (you probably have missed that part).

Erich

LikeLike

Hi Erich!

It is also important to note, that your Dockerfile requires to build the docker image at the first run. As you are using Ubuntu-24.04 it could be assumed that the apt package repositories will be available until 2034.

So this would mean that you would be required to change your Dockerfile in 2035 to point to some alternative apt repos which hopefully will still host the tools you need to install.

This also goes for the wget commands, which might get a 404 in the future.

If you would like to really make it work for the long run (as you have mentioned 10-15 years), you might consider pushing the created image to your docker registry. This could be your local Community Edition Gitlab, or any other suitable location.

But I very much like your idea, this is what I have had in my mind since the whole docker technology started to get momentum. Especially handy in large organizations, where due to the complexity of toolchains it literally takes 1-2 days for a new dev to be able to compile the project locally.

Using this it is now only a matter of a git clone and opening VS Code.

LikeLike

Yes, that’s correct: Docker in that way is not a solution for longevity. Keeping a docker image (not the recipe) is only a way to mitigate some of the challenges, assuming that docker still exists and can use that docker image from a repository. Actually I keep some pre-built docker images as well on dockerhub, but who knows how long this will work, or what if dockerhub changes or docker goes out of business?

But there is hope that with the broad existence of docker it might survive in one or the other way. If we think about critical infrastructure used today (git, docker, gcc, or even the internet), then things get pretty scary.

But to your last point: yes, this is what I had actually in mind exploring DevContainer with VS Code: it has been very challenging to get a class of students up and running quickly with the lab infrastructure, and DevContainer certainly help with that. Plus, it is very transparent, you still see the tools and parts needed. This in contrast to ‘complete and full installers’ which are nice, but hide imho the necessary building blocks too much. So I prefer something which is transparent and which I can tweak over such an ‘all-in-one-installer’.

LikeLike

The awful mess of the Windows kernel API vs the reliable stability of the Linux kernel adhering to POSIX is the reason why docker container are so useful and windows containers are now pretty much abandoned by Microsoft and potential users.

LikeLike

I never ever used Windows in a container.

LikeLike

Hi Erich,

Great article, thank you!

Being able to rebuild things easily down the road is important.

I think docker containers are a nice option, especially under Linux.

The safer option for longevity in my view is Virtual machine.

And then that also means that the VM needs to be tested on another host,

and more importantly can not contain any software which is locked to the host.

Ideally, it also does not use another locking mechanism (license server, dongle) as it is unclear if these will still work in 10+ years (is the company who provided the tool even still around? Will they help you to move the license? Will they even be able to do it?)

So short:

Set things (build environment) up in a VM and make sure nothing is locked to host, dongle license server is my recommendation.

It obviously also affects the selection of tools (compiler):

I recommend: Nothing that requires a locked license to run.

LikeLike

Hi Rolf,

imho, VM’s are maybe better thand docker/containers, but still there is no guarantee that the VM will continue to work.

I agree with the point about locking/licensing mechanism: that would add yet another dependency, best without any licensing check constraint.

To me, the best way to keep things is having multiple approaches, which can indeed include a VM image. But at the end I think for really important projects it might make sense to keep the development machine securely stored and checked in a regular way (mechanical parts, electronic parts, etc), with in parallel keeping a ‘moving’ modern environment going forward. Expensive, but anyway only for ‘expensive’ or important projects.

LikeLike

Hi Erich,

It seems we agree that a VM is a good approach for longevity.

The avoidance of a hard licensing check (that prevents you from using it if dongle or license server is not found or CID changes)

to me is equally important. A VM that only works if the dongle still works is nothing I would want to rely on.

I would rely on just a VM. IMHO and experience, there is always a way to fire up an old VM.

I can use 16-bit x86 compilers in old VMs and I can still run (and build!) Apple II programs in an emulator.

Software with copy protection / Hard license checks are a problem, hence best avoided.

And on keeping the old machine: Does not hurt, but not necessary in my view once the VM is known to work.

And even if not super important, I like to be able to rebuild stuff I created 30+ years ago on today’s laptop.

LikeLike

These may not affect hobbyists or academics, but there are restrictions on using Docker Desktop: companies with more than 250 employees OR more than $10M in revenue need a paid subscription:

https://www.docker.com/pricing/faq/

As a replacement, I found a way on Windows 11 to run the free Docker Engine on Ubuntu WSL2 that is started automatically with WSL2 and to access it from Windows transparently by combining ideas from these discussions and tools:

https://blog.avenuecode.com/running-docker-engine-on-wsl-2

https://askubuntu.com/a/1356147

https://github.com/HanabishiRecca/WslShortcut

This enables to type commands in the Windows shell directly like this:

PS > docker image ls

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

portainer/portainer-ce latest 3c6403908069 4 months ago 302MB

dockurr/windows latest d4ef1781f2ca 12 months ago 431MB

vsc-core-19e32c148eda9be582235c93e2081af0d9e991c18c4d9ad3a1c2b54b8a8c79b6 latest eb5b159bfa0c 14 months ago 2.15GB

vsc-volume-bootstrap latest 6fa28b22f2fc 14 months ago 784MB

hello-world latest d2c94e258dcb 22 months ago 13.3kB

It even works from VSCode Docker extension.

LikeLike

Yes, indeed Docker is not free for larger companies. Thanks for the idea about accessing it directly in WSL2!

LikeLike